In January 1904 the Hereros rise in arms

The missionaries had asked in vain their protégés not to buy too uncontrollably from the Germans. And in vain they had asked the Herero chiefs not to cede any land to the traders. And finally, also in vain, they asked the colonial administration to set up reservations for the Hereros.

In mid-January 1904 the Hereros rise in arms. More than 100 Germans are murdered within a few days. The answer is harsh - and the months of fighting are becoming increasingly cruel.

Most Germans had originally a positive image of the "Negroes" or "Mohrs", as they were called at the time. The black African saint S. Moritz (Mauritius) became the patron saint of the Magdeburg Cathedral during the early Middle Ages. In the 18th century, Mohr Amo, who worked in Brunswick, was even able to become a professor at the University of Wittenberg. And 100 years later writers like Harriet Beecher-Strone and Karl May drew the picture of the noble native.

As a young girl, Else Sonnenberg also had this dream in mind: to create a peaceful community in a beautiful country together with the locals. That dream is now bursting like a soap bubble. The language with which the "Braunschweiger Landeszeitung" describes the events in the distant colony is indicative of this. At the beginning of the rebellion, it is still relatively factual that the Hereros ("a powerful tribe of 30,000 to 40,000 people") know how to fight valiantly. But then the language becomes increasingly shrill, racist and finally inhuman. Already on 19 January 1904, one can read: "There can be no other means of information than the suppression of the rebels with all ruthlessness, which is able to compel the uncivilized tribes with all respect and obedience." On February 22nd, there is the talk of a "bloodthirsty horde of negroes" that rages horribly with the "bestiality of semi-wild animals" (March 13th). Almost all of the horror stories turned out later to be grossly exaggerated. But they shaped the image of the "Negro" and burned themselves deeply into the collective subconscious of the Germans.

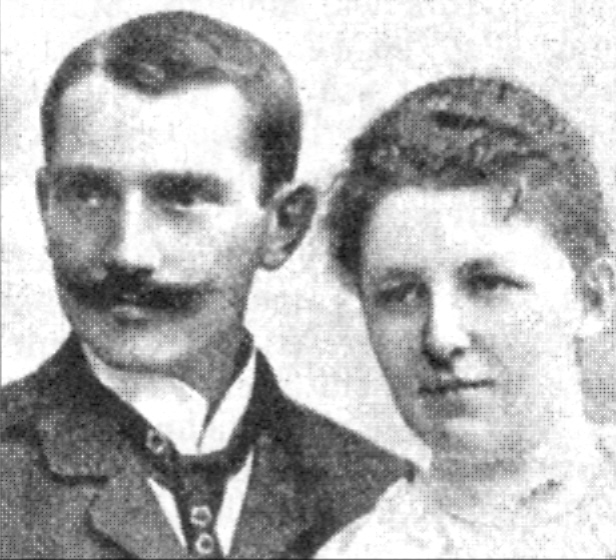

This makes Else Sonneberg's behavior all the more astonishing. She would have had every reason to report resentfully about the Hereros. After all, it was her own servant Ludwig who had killed her husband. She and her child had initially found refuge with missionary Eich. After almost three months in captivity is she allowed to move with him to her fellow countrymen in Okahandja or Windhoek.

"The faithful suffer whether they are black or white"

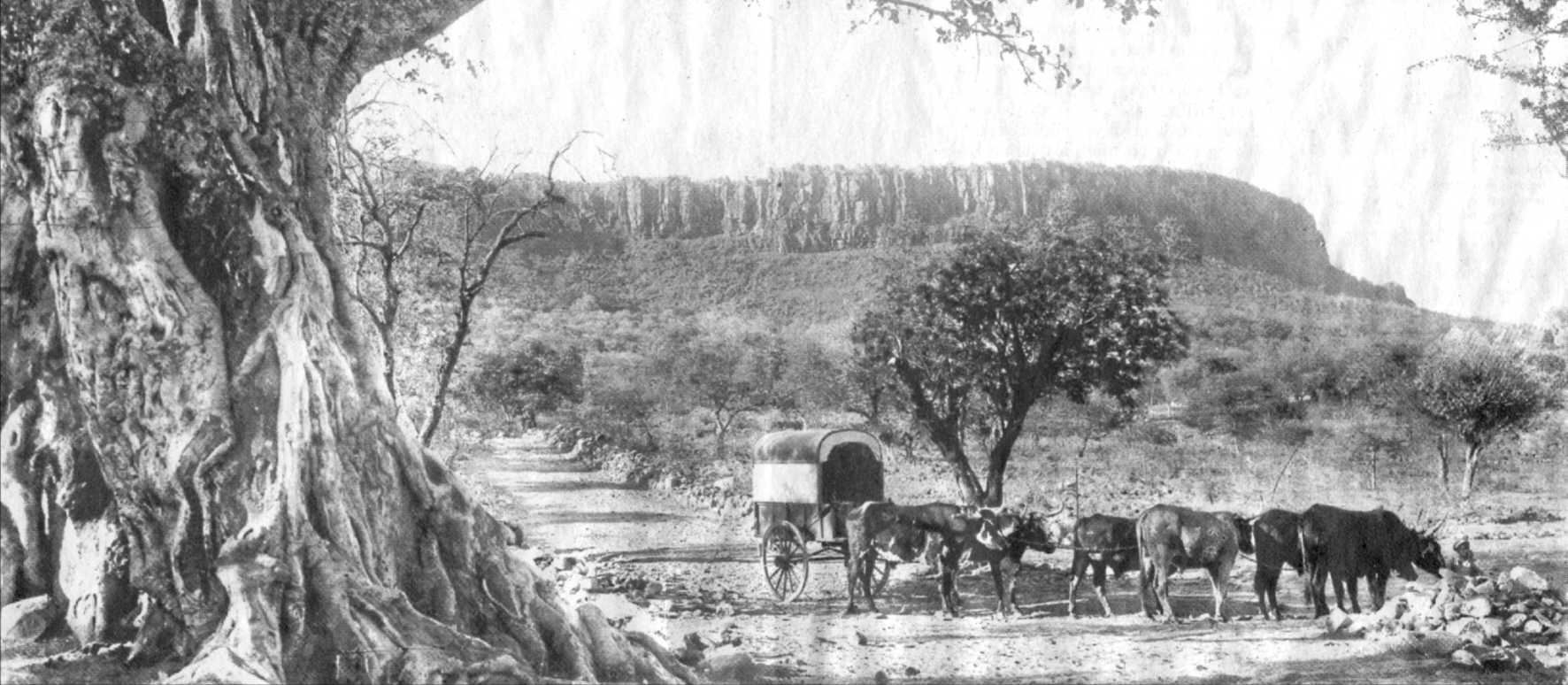

At the end of 1904, Else Sonnenberg returned to Germany as a young widow with her young son. She published her experiences in the book "How it was at the Waterberg" in 1905. There is no talk of revenge or disgust for the deeds of the Hereros. In addition to her understandable grief, Else Sonnenberg did not let the beautiful images of Africa be stolen from her.

As one of the few contemporary witnesses, she reported on the war in a differentiated manner. She was aware that the innocent in particular had suffered: "The faithful have to suffer for the sins of the unfaithful, whether they are black or white."

With her son Werner - he later emigrated to Brazil - Else Sonnenberg has returned to her parents' house in Wendeburg. There she was allowed to grow old with dignity until her death in 1967. When the over 80-year-old woman's eyesight faded, she said to the local home attendant Otto Helms: "I've seen so much of the world that I keep in me. The picture remains - I can look back on many beautiful things."

The Wendeburg publishing house Uwe Krebs

has published some years ago an attractive reprint of Else Sonnenberg's book

(124 pages/15 Euro). The explanatory volume

was published in parallel. Written by Otto Pfingsten (63 pages, 10 Euro).

The above report was published in the Braunschweiger Zeitung on 10 April 2010.

Many thanks to the Uwe Krebs publishing house and Mister Otto Pfingsten. They were so kind to allow the use of their material.